Esgar ‘the Crippled’ - disability before the Norman Conquest

Exon Domesday is the surviving record of an earlier stage of the Domesday survey of England in 1086, covering a circuit of the South-West of England. It records the individuals who held land in 1086 and those who had held it in the reign of king Edward before the Conquest, along with its worth. Presumably, similar early-stage documents for each area of England were produced, although these no longer survive. The final product of these surveys, written up into new form, we now term Domesday Book. An online edition of Exon Domesday, including both pictures of the manuscripts and a modern English translation, is freely available online (https://www.exondomesday.ac.uk/).

Esgar - Pre-Conquest Landowner

Exon Domesday is a huge and complex source, so today I’m going to pick out just one individual: Esgar, who is usually given the nickname ‘the Crippled’ (on the unsuitability of this term, see below). Esgar appears twice in Exon Domesday, from which it is clear that he held land in England before the Conquest:

The king has 1 estate which is called Ermington, which Esgar the Crippled held on the day that King Eadweard was alive and dead, and it paid geld for 3 hides.1

and

The king has 1 estate which is called Blackawton, which Esgar the Crippled held on the day that King Eadweard was alive and dead, and it paid geld for 6 hides.2

One of the manuscript pages in which Esgar is mentioned. Source: https://www.exondomesday.ac.uk

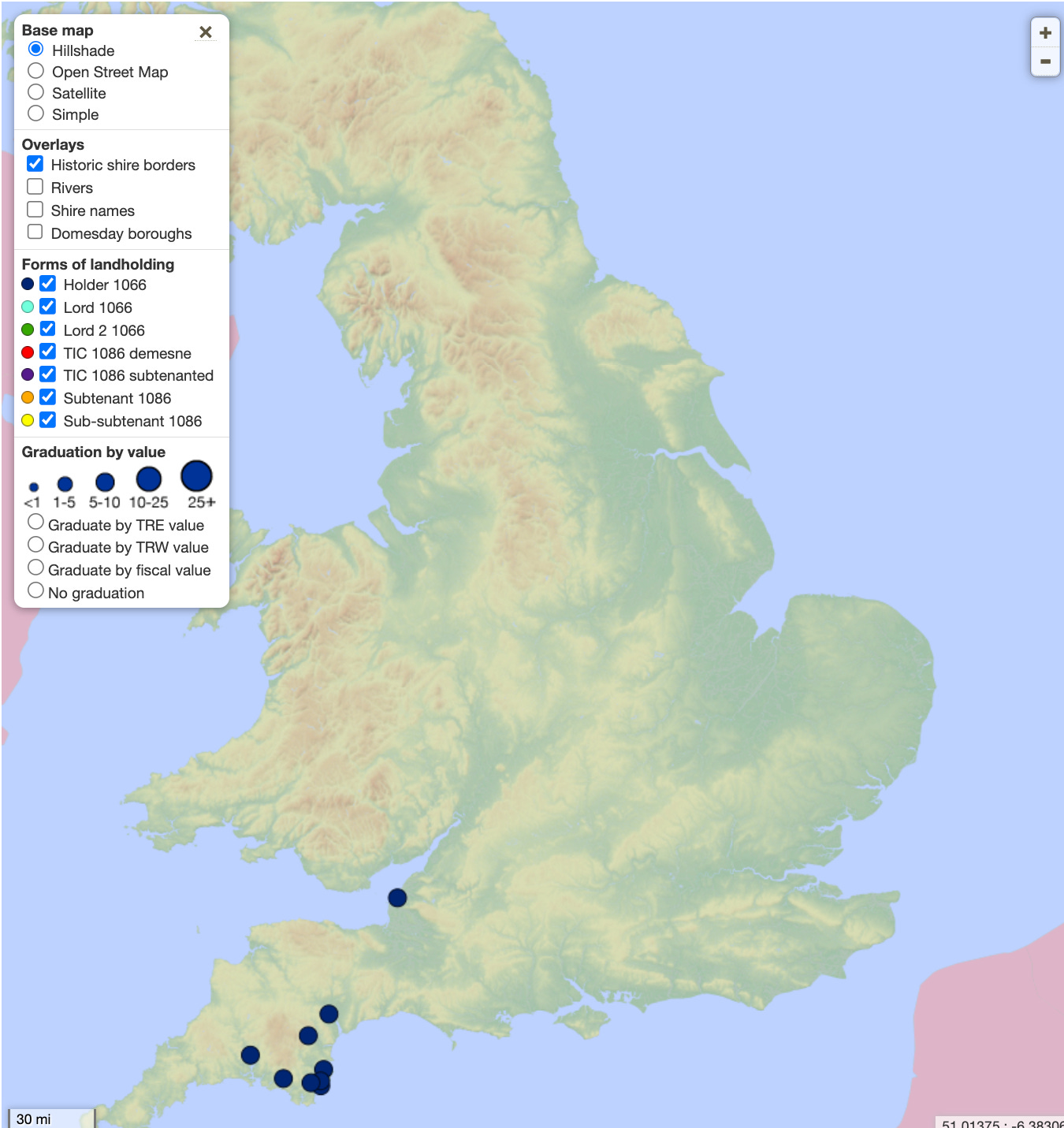

Esgar also appears in the Domesday Book itself, notably without his nickname.3 The text attributes to him a number of holdings, primarily in Devon (see map below).

Photo Source: https://domesday.pase.ac.uk/Domesday?op=5&personkey=38881

Using Esgar to ask Questions

Esgar raises two interesting questions. The first, explicitly onomastic, is the suitability of his nickname. To a modern audience, ‘cripple’ is rightly an offensive term, with a long history of exclusion and mockery. It’s no longer a medical term but one of a broad range of now unacceptable terms used to ‘Other’ physically impaired individuals. Our question, then, is whether this was the intention of the original terminology too.

The second is much broader. If, as seems likely, this nickname denotes an individual somewhere within the disability spectrum, it presents a perfect chance to explore the perception and reception of disabled individuals in pre-Conquest England. Disability is sometimes historically visible, either in written texts, especially within the act of being miraculously ‘healed’ by religious figures, or from osteo-archaeological evidence (the study of human bones). Far more frequently, however, it is not. In order to combat the lack of evidence we have for disabled individuals in early medieval England, of how they were treated, can we use the onomastic evidence to begin to explore how Esgar’s was seen by his contemporaries?

‘The Crippled’ - A World of Translation (and Interpretation) Issues

Esgar’s nickname appears in Latin in the text, as Contractus. Any translation is a delicate art, but terms of physical ‘disability’ are often particularly hard to translate; the Medieval Disability Glossary illustrates this well. The reason for this is, fundamentally, theoretical.

A consistent trend in modern academic history has been to challenge ideas that we have traditionally seen as straight-forward and monolithic. Real life is rarely this simplistic. Variation across time and space makes clear that many cultural trends of the modern world are culture-specific trends, and vary substantially across history. Recently, incredibly fruitful research has been conducted in the realm of Gender and Sexuality. Another crucial topic is ‘Disability’.

In a modern sense, we tend simply to identify any physical (and, increasingly, mental) divergence from the ‘norm’ as a ‘disability’. However, Shakespeare (not the playwright) has drawn an important social distinction between ‘Impairment’ and ‘Disability’. The former is a physical or mental ailment; it is biological and physiological, and a medical condition. This, in reality, is what we mean when we say someone is ‘disabled’ in modern terminology. ‘Disability’, however, is the social exclusion a culture applies to an impaired individual: the ‘Disabled’ individual is considered an ‘Other’ in society, different and excluded. An individual is born impaired or develops an impairment during their lifetime, but it is a society that MAKES them ‘disabled’.

What is considered as ‘disabled’ therefore varies by culture, and within a culture. Questions of status, gender, and occupation and all relevant. So is the question of religion: is impairment considered a punishment from some kind of deity? Is it subsequently considered a moral failing?

It’s clear that nicknames function, across almost all cultures and times, to help distribute power; we give praising nicknames to people we like and mocking ones to those we want to exclude. So when we translate and interpret Esgar’s nickname, we need to ask a (deceptively) simple question: what was its purpose? Was his nickname an attempt to mock and exclude Esgar for a physical impairment, marking him out as physically different? Was it instead intended as a simple observation for a medical condition?

The Exon translation (by Thorn) suggests ‘crippled’ as a probable translation, and this has been broadly accepted. Tengvik, who compiled a number of English nicknames in his thesis in the 1930s, opts instead for ‘mutilated, maimed’.4 These are both decidedly 'disabling' in modern English. If Esgar’s nickname was intended to mock him, is applying a mocking modern English term fitting, in order to mirror the weight and intention behind the nickname? But is this necessarily the case?

It’s immediately clear that Esgar was not, by any means, completely excluded from society; his landholdings in pre-Conquest England are not insubstantial. We can draw an interesting parallel with Hermann, a German monk of the 11th century, who is also given the nickname Contractus. Hermann produced a wide range of historical and musical texts, and he ‘surpassed all the men of that time in wisdom and virtues’.5

Broader vocabulary use is also interesting. Bruce suggests that the Old English word unhælu is most closely allied to a modern concept of ‘disability’. This does not appear anywhere as a nickname; nobody is nicknamed 'the disabled’. Furthermore, adopting a broader look at the data, the majority of nicknames that we might consider referencing disability mention specific body parts; Eadmær 'One-Handed', Humphrey 'Club-Foot', Ralph 'Twisted Hands' etc. Is Contractus in fact being applied to a specific medical condition, rather than adopting the generalised and offensive terminology it takes on today? Is it more appropriately not translated as ‘Crippled’?

So where does that leave us? I’m afraid as of yet I have no simple answer (lay off, I’m only halfway through the PhD…). Even in the case of Esgar, where Domesday Book provides economic and social data to contextualise individuals, we simply do not have enough evidence to concretely suggest how Esgar was perceived by his peers. But beginning to ask these questions, about the power of nicknames to create an individual’s public perception and how that might interact with concepts of disability, is the first step. Sign up for the newsletter below and I’ll keep you up to date when I find more answers!

https://www.exondomesday.ac.uk/digipal/manuscripts/1/texts/view/?center=translation/sync/location/;&east=transcription/sync/location/;&north=image/sync/location/;&above=location/entry/85b1/;

https://www.exondomesday.ac.uk/digipal/manuscripts/1/texts/view/?center=translation/sync/location/;subl:%5B%5B%22%22,%22location%22%5D,%5B%22loctype%22,%22entry%22%5D,%5B%22@text%22,%2285b8%22%5D%5D;&east=transcription/sync/location/;&north=image/sync/location/;subl:%5B%5B%22%22,%22location%22%5D,%5B%22loctype%22,%22entry%22%5D,%5B%22@text%22,%2285b8%22%5D%5D;olv:7,5272,-3948,0;&above=location/entry/85b8/;subl:%5B%5B%22%22,%22location%22%5D,%5B%22loctype%22,%22entry%22%5D,%5B%22@text%22,%2285b8%22%5D%5D;

This system of onomastic simplification between the earlier outputs of the survey and the Domesday Book-proper is a fascinating phenomenon, for which I do not yet have an explanation.

Tengvik, G. Old English Bynames (Uppsala, 1938).

Berthold of Reichenau, ‘Chronicle: The First Version’ in I. S. Robinson (ed.), Eleventh-Century Germany: The Swabian Chronicles (Manchester, 2013), 99.