Westfield Farm – a High-status ‘Anglo-Saxon’ Female Burial

We hear an awful lot about the large-scale male ‘Princely’ burial of the early seventh century; Sutton Hoo, Snape, and Prittlewell dominate the narrative on richly furnished burials. These are wonderful and historically significant sites, and have important things to say about emerging networks of power and status. But by focusing on the presentation of masculinity alone we are restricting our knowledge base to a single, gendered outlook: what of high-status women during this period?

Rich ‘princely’ male burials group around the first quarter of the seventh century, and then they disappear as quickly as they arrive. In their place emerge lavishly furnished female burials, centering on the later part of the century and peaking in the 660s. Is this change in burial focus a movement in society towards a new focus on how power and legitimacy was conferred and re-enforced?

One of the prime examples of this later trend in richly furnished female burials is found at Westfield Farm, Ely. You can find a free online site report for this site here. Let’s take a look at it in a little more detail (not too much, mind!).

Cemetery

Rather than a single burial, Westfield Farm involves a cemetery, and this collection of burials appears to centre around Grave 1, potentially originally covered by a mound. Osteoarchaeological evidence suggests this is a female aged 10 to 12.

Finds

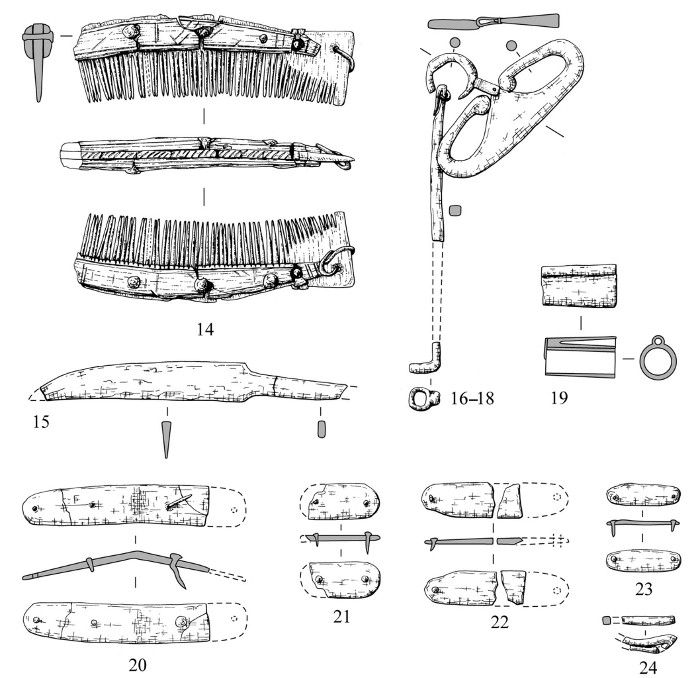

The central Grave 1 is accompanied by a number of notable finds. The explicitly Christian context of the grave would seem to be established by a cruciform pendant.

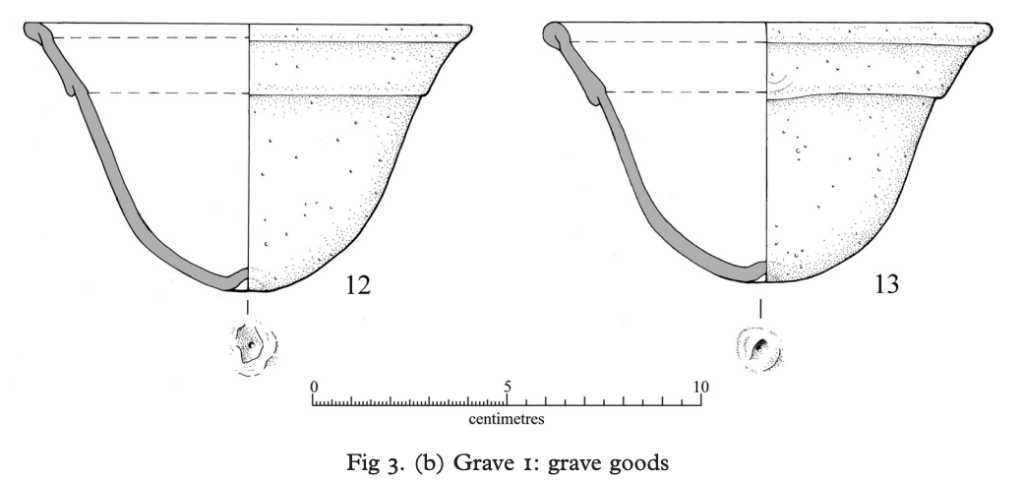

A set of green glass palm-cups were also found associated with the body. The presence of glass vessels is usually interpreted as a sign of impressive prestige and status, as with the glass claw-beaker found in the ‘Princely’ burial at Snape.

The remains of iron bindings appear to illustrate the presence of a casket or box, the wood of which has by now long rotted away. The presence of a padlock key would seem to suggest that this box was lockable, and access to it was (symbolically) controlled by the deceased individual.

Female Lavish Burials

So, why the shift from elite male lavish burials in the first quarter of the 7thC to female equivalents in the latter half of the century?

Hines and Bayliss (2013, p. 542) have suggested that the shift to women was the result of it no longer being acceptable to bury men with weapons in a Christian context. But Hamerow disagrees with this – it would have been perfectly possible to express status in other manners with male burials. What about expensive Christian jewelry, for example - St Cuthbert certainly has a rather spectacular example of this? Why use women’s burials?

Instead, Hamerow argues that it is the symbolism of women that is being foregrounded in the new system of power and legitimacy, and women’s roles in creating dynasties and as religious specialists. It’s worth quoting Hamerow in full:

‘It is argued that these well-furnished graves reflect a new investment in the commemoration of females who came to represent their family’s interests in newly acquired estates and whose importance was enhanced by their ability to confer supernatural legitimacy onto dynastic claims.’ (Hamerow 2016, p. 426)

Do you have loads of spare money just lying around your house, collecting dust? Fancy giving it to a graduate student with no income who will spend it on socially-responsible things like (gluten-free) beer? If you answered yes to these questions, you can donate here.

Bibliography

Hamerow, H., ‘Furnished female burial in seventh-century England: gender and sacral authority in the Conversion Period’, Early Medieval Europe 24/4 (2016)

Hines, J. and Bayliss, A., ‘Anglo-Saxon Graves and Grave Goods of the 6th and 7th Centuries AD: A Chronological Framework’ (London, 2013)

Lucy, C., Newman, R. et al., ‘The burial of a Princess? The later 7th-century cemetery at Westfield Farm, Ely’, The Antiquaries Journal 89 (2009): 81-141.

Newman, R. (2007). Westfield Farm, Ely: An Archaeological Excavation. Cambridge: Cambridge Archaeological Unit. https://doi.org/10.5284/1003392 (https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/library/browse/issue.xhtml?recordId=1101721&recordType=GreyLitSeries)